My father, Khushwant Singh, passed away just over a year ago, at the age of 99. He went peacefully, just as he had wanted, his mental faculties quite intact, though he had become rather deaf in the last couple of years of his life. He was doing a newspaper crossword puzzle on that last day — his daily morning routine — when he felt tired, and lay down on his bed. He did not get up again.

He had been somewhat physically frail towards the end of his life, which bothered him since he had prided himself on his fitness. He played tennis regularly till his mid-80s, and took long walks at the nearby Lodi Gardens. When up in the hills, he walked all over the Kasauli and Simla hills, sometimes walking from Simla to Kasauli and from Kasauli to Kalka, arduous treks. He also enjoyed his evening two “Patiala” pegs of single malt whisky and loved sea-food, particularly golden fried prawns.

In the evening, between 7 and 8, his living-room became an eclectic salon, drawing some of the best and brightest in India and abroad. Beautiful women would sit adoringly at his feet, which is how he got a reputation of being a “dirty old man”. Anybody who rang up to make an appointment was invited. Pakistanis were particularly welcome. There was stimulating talk, gossip, jokes, Urdu poetry, and much else, some of which found its way into his columns. And, needless to say, drinks flowed, since my father kept a well-stocked bar, most of the bottles gifted to him by his admirers. “Are you a drinking person?” my father would invariably ask the visitor. He would be visibly disappointed if the answer was in the negative. Despite his fondness for single malt, he rarely crossed his limit of two pegs and was never drunk. A soiree at Khushwant Singh's Sujan Singh Park flat or in his Kasauli “Raj Villa” bungalow in the Himalayas became much sought-after. But at 8 pm sharp, everybody was asked to depart (only a privileged few were asked to stay on for dinner). He was a stickler for punctuality and made his displeasure plain when anybody, however important, was late.

When I became Editor of the Reader’s Digest (my father had just been made Editor of the Illustrated Weekly of India), my Managing Director invited both of us for dinner to his home. He wanted to show off my father to some of his friends. We arrived at his home, at the appointed hour, 8 pm. The host was having a bath, the servant informed us. My father waited patiently for ten minutes. When no host appeared, he told me that I could stay on, but he was leaving.

“Where’s your father?” my MD asked me, when he finally appeared after his bath. “I’m afraid he left, as you had called us at 8,” I replied. He had a difficult time explaining to his friends why my father was not there.

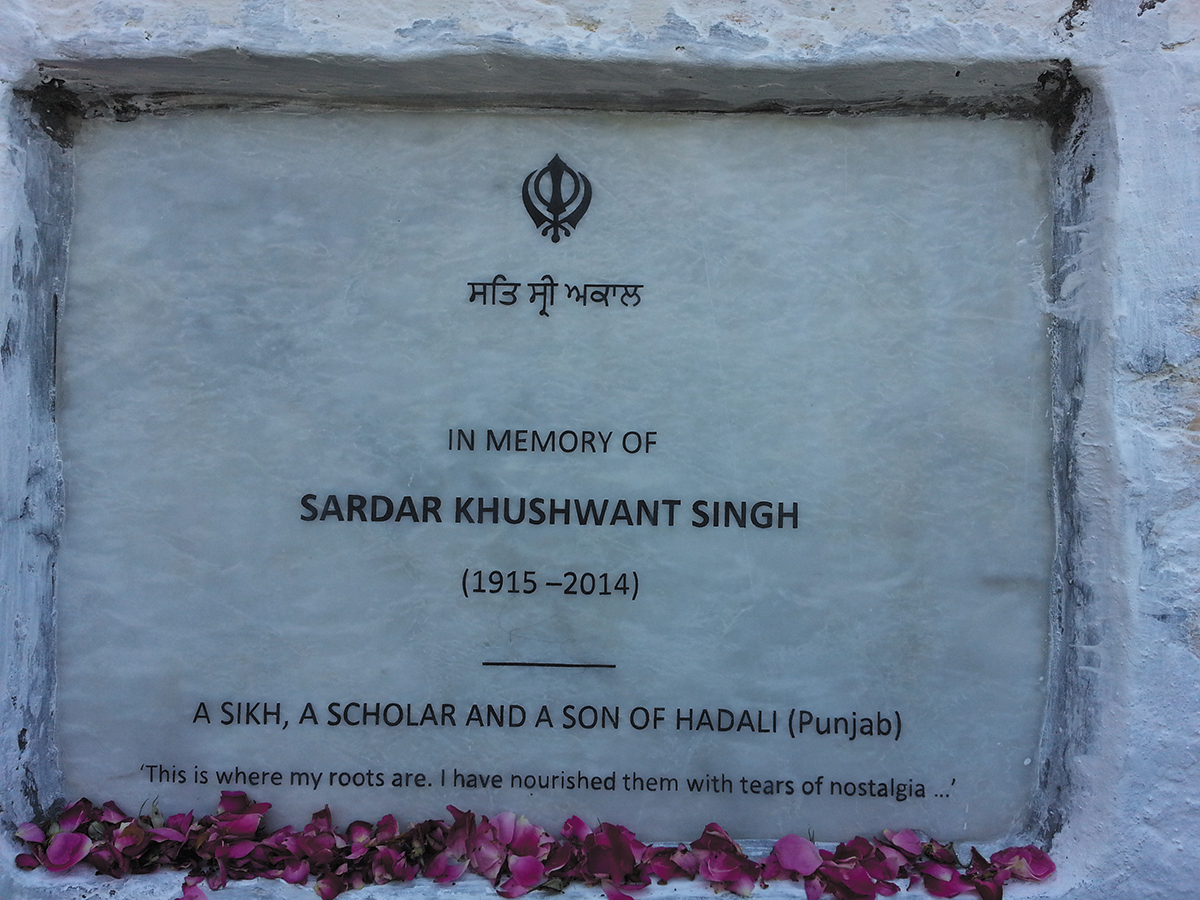

The memorial plaque on the wall of the government school Khushwant Singh went to in Hadali, Pakistan. Photos: Rahul Singh

Lord Swraj Paul, a regular visitor, once told me that he always came a few minutes early to my father’s place, knowing the ways of Delhi traffic. He spent those minutes pacing up and down, outside the flat. Then, on the dot of 7, he would ring the bell. Once, a BBC TV team that had come to interview him, turned up half an hour late. My father was livid. “Tell them they are not welcome,” he ordered me. The BBC interviewer and cameraman pleaded with me, apologising for the delay. My father was adamant. The interview did not take place.

After his two drinks, he would have a light dinner at 8 (he rarely socialised outside his home, unless with close friends, or if he was travelling), watch some TV (Barkha Dutt was a favourite — her mother, Prabha Dutt, had been his chief reporter during his Hindustan Times days), do a little reading before going to sleep at 9. He would be up by 4, make his own tea and get to work. Then, tennis at the Delhi Gymkhana in the early morning, and back again to work. Lunch was usually a soup, followed by an hour-long snooze, and then yet more work, with a walk or a swim in-between.

Soon after he died, there was an amusing tweet on the Internet which went viral: “Iyengar (the famous Yoga guru) was a vegetarian and a strict teetotaler. He died at 84. Khushwant Singh ate meat and regularly drank alcohol. He died at 99.” Jokes aside, my father was a glutton for work. His output of around 150 books speaks for itself. He also wrote probably the longest running weekly column in India, probably in the world, “With Malice Towards One and All”. It was also hugely popular, read by tens of millions of people and being translated into several Indian languages. He first started it in the Illustrated Weekly, when he took over its editorship in 1969 and then moved it to Hindustan Times, where it continued till a few months before he passed away — a total of some 45 continuous years, every week! He started another weekly column for the Chandigarh Tribune, called “This Above All”, which ran for some 30 years and was also translated into other Indian languages.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated

Rahul Singh’s piece on his father turns out to be a damp squib. In your magazine one wouldn’t be expecting a second rate essay of gossipy style. All these trivialities and peculiarities of Khushwant Singh are known to readers for a long, long time. What would have been interesting is a serious and critical evaluation of his writings in general or a specific book or novel. It is time someone should take up the task for posterity.

Surjit Kohli

Aug 22, 2017 at 14:47