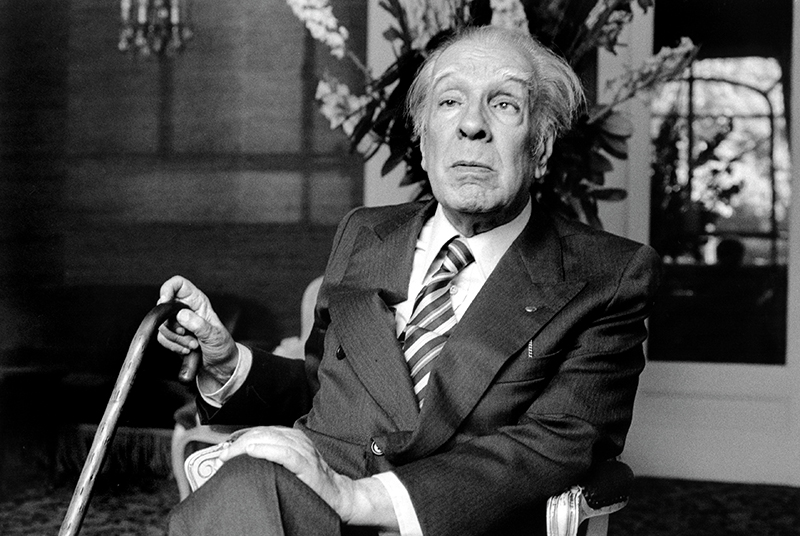

Jorge Luis Borges. Photo by Ulf Andersen/Getty Images

Introduction

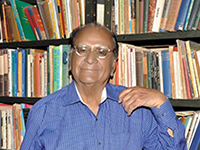

Novelist, short story writer, essayist, poet and translator, Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on August 24, 1899. When he was only nine, Jorge Luis Borges translated Oscar Wilde’s story The Happy Prince into Spanish. In 1914, his family moved to Switzerland where he attended school, receiving his baccalaureate from the College de Geneve in 1918. On his return to Argentina, he started his literary career, publishing his poems and essays in various journals. He also took position as a librarian and delivered public lectures all over the country. In 1955, he was appointed director of the National Public Library and also as professor of Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. In 1961, he won international recognition when he received Prix International award, together with Samuel Beckett. In 1971, he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize for Literature.

Since he was now an internationally reputed writer, his works were translated and published extensively in Europe and in the United States. He was himself proficient in several languages. His work derives its power (verve) from his use of fantasy and unreality as its basic element. His most renowned publications are Ficciones (1944) and The Aleph (1949) which are compilations of his stories structured around such themes as dreams, animals, labyrinths, fictional writers, religion and God, magic because he reacted strongly against realism and naturalism. It was his blindness which enabled him to create this world of fantasy. His literary reputation reached its climax during the “Latin American Boom” when writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez (author of One Hundred Years of Solitude) appeared on the literary scene. To quote J. M. Coetzee, Borges, — more than anyone, renovated the language of fiction and thus opened the way to a remarkable generation of Spanish American novelists. During his last years, he did feel quite disillusioned over missing the Nobel Prize which most of his contemporaries felt that he richly deserved. He died in Geneva, Switzerland, on June 14, 1986, at the age of 86.

When Franklin & Marshall College, where I was visiting professor during 1982-1984, announced that it had invited Jorge Luis Borges to deliver a special lecture on campus, I was excited like a youngster who was to meet his idol. I had always admired Borges as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth-century. In fact, I always felt that if any writer deserved to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was Luis Borges. But, unfortunately, he never made it to the Swedish Academy. All his admirers thought that Stockholm had unjustifiably denied this great Argentine writer his rightful claim to the Nobel Prize. As for Borges himself, I read somewhere that he was utterly frustrated to have been denied this award. In fact, he was supposed to have stated, somewhat bluntly, that the Scandinavian tradition had often bypassed the real deserving writers.

Before Borges’s arrival on campus, I requested the Chairman of my Department of English, Prof. Sandy Pinsker, to let me have a couple of private sessions with this great writer after his public lecture.

He assured, “Certainly, ‘I’ll arrange to let you have breakfast and lunch with him at the Guest House of the college.”

Another thing that attracted me to the lecture was the subject — Emily Dickinson, an American poet I adored very much. I was so enthusiastic about his appearance on campus that I encouraged my students to attend his lecture at the Marshall auditorium.

Then arrived the great moment. Prof. Pinsker escorted Borges to the dais and introduced him as one of the most distinguished literary celebrities of the century. His blind eyes pulsating with some inner energy, Borges gathered himself upon his feet holding his stick in his right-hand. He began in a voice that was deep and sonorous, saying that he was honoured to be present on the campus of a renowned liberal arts college of the USA. Then he started his lecture on Emily Dickinson, saying that his favourite line of the poet was that it is “The wounded deer that leaps highest in the air”. “I take this line as something that strikes a personal note within me, because my visual handicap, which is my deep wound, has enabled me too to leap high in the atmosphere. My favourite writer Oscar Wilde opens his book De Profundis with an insightful statement: “Where there’s suffering, there’s holy ground.”

After striking this personal note, he explained how behind the facade of simple language, Emily Dickinson ventures to probe the deeper recesses of the human heart and mind.

He was another John Milton, who never allowed blindness to come in the way of his writing. All night I imagined Borges pursuing courageously his ambition to innovate a new style of writing.

Next morning, Pinsker took me to the guest house and after introducing me to him as a professor and writer from India. He left me to converse with him. As I sat across the breakfast table, I said, “Dr Borges, I am supremely privileged to be with you this morning. I don’t wish to embarrass you with my accolades for your writing. But I do want you to know that I earnestly believe that you are one of the greatest luminaries in the contemporary literary world.”

“I am happy to hear this from a friend from India — a country which I love and admire. You know, during my stay in Europe I learnt German which brought me to Max Muller’s classical book, Sacred Books of the East. My favourite book in this series was the Mahabharata and, you may understand, why I was touched by the character of Dhritarashtra.”

“I can quite understand what you’ve in mind, because Dhritarashtra said to Sanjay, his companion, that blindness was the greatest affliction that could befall a man.”

“As we are talking informally like two friends let me tell you that I inherited my visual disability from my father who began to lose his eyesight in his thirties. This physical handicap brought me close to my mother who, in my later years, acted almost as my secretary. I often dictated my poems, stories and essays to her. Thus I forged a very special relationship with my mother. In fact, my mother was my greatest prop in life. I was her darling and she was my greatest source of comfort.”

“So was I my mother’s darling,” I interposed. I went on to share with Borges an incident from my early childhood, carried away as I was on the crest of my nostalgia. “I was just four years old when my mother took me out with her to a stream about a couple of miles outside our village. That’s where she often went to do her washing. We left early morning after breakfast. While she did the laundry by the bank of the stream, I looked at the clouds imagining all kinds of faces peeping at me from the sky. I lost all track of time. When she had done it was noon time. The sun came out in the sky with its blazing heat. I realised that I’d walked barefoot with my mother from the village to the stream, while she was wearing her leather chappals. It was now time to start walking back home. I suddenly realised that the ground under my feet was burning like hot coals. I cried out. My mother understood that my feet couldn’t endure the scorching heat. At once she took off her own chappals, too large for my feet, and asked me to wear them, while she started walking barefoot. We’d hardly gone a few yards when I saw her almost leaping upon her feet like a kangaroo. I understood (knew) that her feet were burning and she couldn’t possibly walk normally. I said, ‘Mom, I should be able to walk barefoot. Why don’t you take back your chappals?’

‘No, my dearest, no it’s not bothering me at all.’ All the way I could see she walked painfully hopping on her feet. When we reached home she dipped her feet in a bucket of cold water, but it didn’t do her any good. Then she applied butter cream on the soles of her feet and lay for a while. I sat near her on the bed, tears rolling down my cheeks.”

“That’s a very poignant scene from your childhood,” said Borges. “Have you used this incident anywhere in your fiction or poetry?” “No,” I replied. “It’s a memory that would remain with me forever. I’ve shared it with you because we’ve both been our mother’s darlings. When she died, I felt that the earth had given way under my feet. I’ve written several poems on my mother’s death.”

“Since I wouldn’t be able to read any of those poems, why don’t you read one of these to me?” he asked, leaning forward.

“Alright I’ll read some lines from one of these poems to you — from my collection Subterfuges. This poem is titled “My Mother’s Death Anniversary”. This is how it they reads:

Each year a day chooses me to feed the dead.

What’s that yellow flame that moves from door to door peering through the chinks

of my heavy draperies? Now that my son has grown

Into an elm

I may go out

to meet the stranger.

“Very touching, indeed,” he sighed. “I particularly like the yellow flame towards the end of the poem — incisively imagistic with a touch of Surrealism.”

“Thank you very much,” I mumbled. “In fact, I’ve brought three collections of my poems for you.”

“Very grateful,” he responded. “I’ll have them read out to me when I return to Buenos Aires.”

There was brief silence after which I said, “In this context, let me recall a scene from the Mahabharata in which the Yaksha, a divine spirit, asks Yudhisthira, the eldest of the Pandavas, as to what is heavier than the earth. At once Yudhishthira answered, ‘The Mother!’”

“Although I’ve read the Mahabharata in German, I should like to read this part of the epic once again.”

There was a long pause in our conversation. Then I resumed, “I’ve read somewhere that you translated Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince into Spanish at the early age of nine. An admirable feat, certainly. I know you’ve translated several other works as well. May I, therefore, ask you about your experience as a translator? Would you consider translation as a sort of creative activity?

“Yes,” he replied. “In fact I remember what a great Italian translator once quipped that in certain cases the translation may excel the original.”

“A remarkable observation,” I said. Then I added, “You manifested your precocity when you had read Shakespeare at the age of 12 — a fact that I picked up from somewhere.”

“You know that Shakespeare had stayed with me all my life,” Borges said. “It was he who initiated me at an early age to the world of fantasy that I was to explore in my own writings.”

“When I first read your story The Labyrinth, I felt like a diver penetrating the deeper layers of a dark underworld. I had, of course, understood that you had blended philosophy, mythology, mathematics, as well as theology into your writing. No wonder, you have remained inaccessible to the common reader.”

“This may bring me back to my visual handicap. I’ve always carried in my mind that line from Shakespeare’s King Lear in which Gloucester says, ‘I stumbled when I saw’. When his eyes were gouged out, his inner eye opened and he began to comprehend the world better.”

I was overwhelmed by the correspondence he had established between Gloucester and himself. He sounded so transparent and candid unlike most writers who always choose to camouflage their personal handicaps.

“Let me tell you something that I’ve learnt in my life,” Borges said. “No one should read self-pity or reproach into this statement of the majesty of God, who with such splendid irony, granted me books and blindness at one touch. When I think of what I’ve lost, I ask, ‘Who know themselves better than the blind?’, — for every thought becomes a tool.”

“Marvelous!” I responded. “I imagine that it was God in his great majesty who held your pen and made you write. How else could you have written a poem like your Hymn to the Sea? May I read this poem to you, please — for my pleasure?” Then I began reading it:

Brother, Father, Lover! ...

I enter the great garden of your waters and swim far away from the earth.

The waves come in with a fragile crest of foam, Fleeing towards failure. Toward the coast, with its reddish peaks,

with its geometric houses, with its toy palm trees,

that have become livid and absurd, like rigid memories!

I am with you, Sea. And my body extended like a bow fighting against your impetuous muscles.

Page

Donate Now

More from The Byword

Comments

*Comments will be moderated